Esophageal foreign body - Coin ingestion

- Age: 1

- Sex: Male

- Modality: X-ray

- Region: Chest

- Country: N/A

- State: N/A

- City: N/A

- Diagnosis: Esophageal foreign body

🧠 AI Suggestion

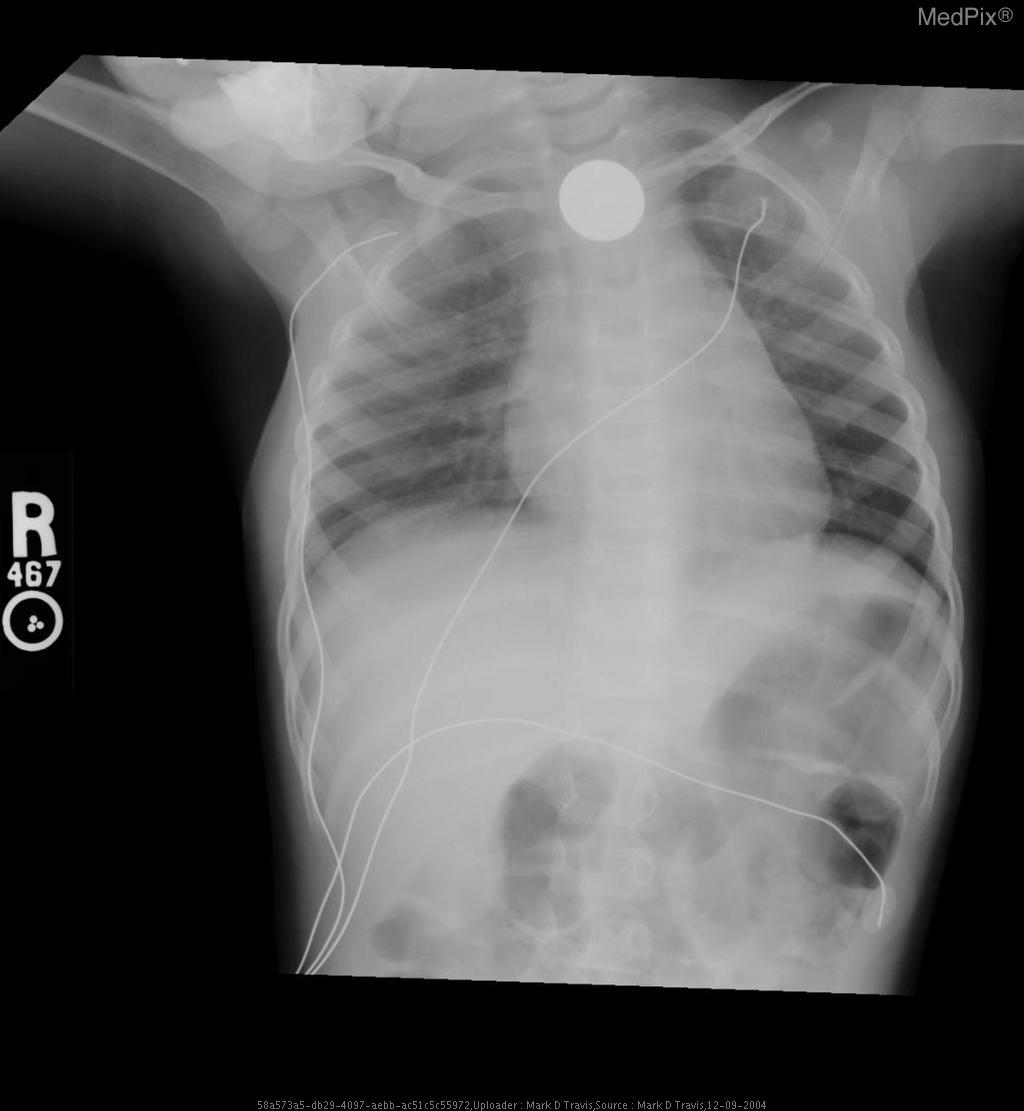

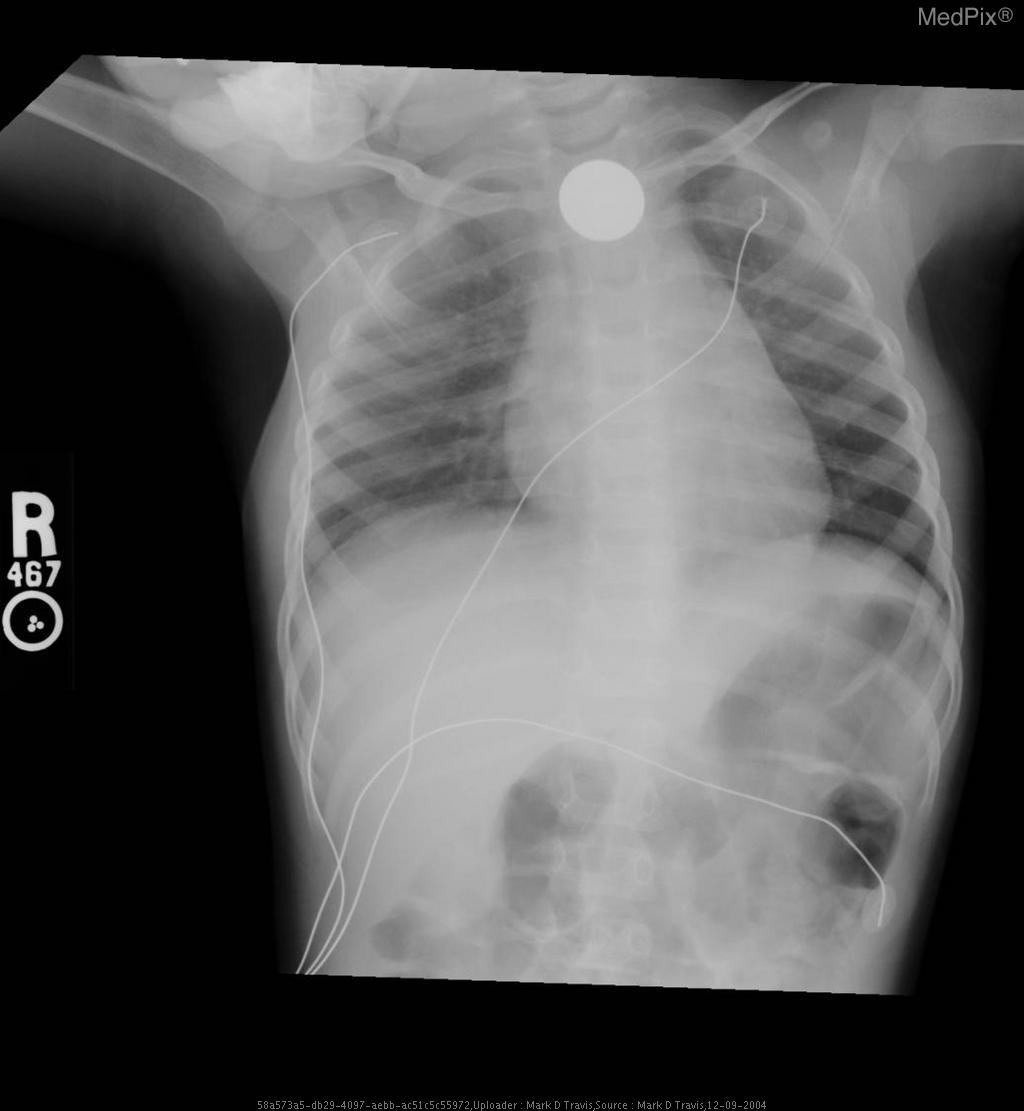

- Frontal chest and upper abdominal X-ray with standard orientation (image-left = patient-right).

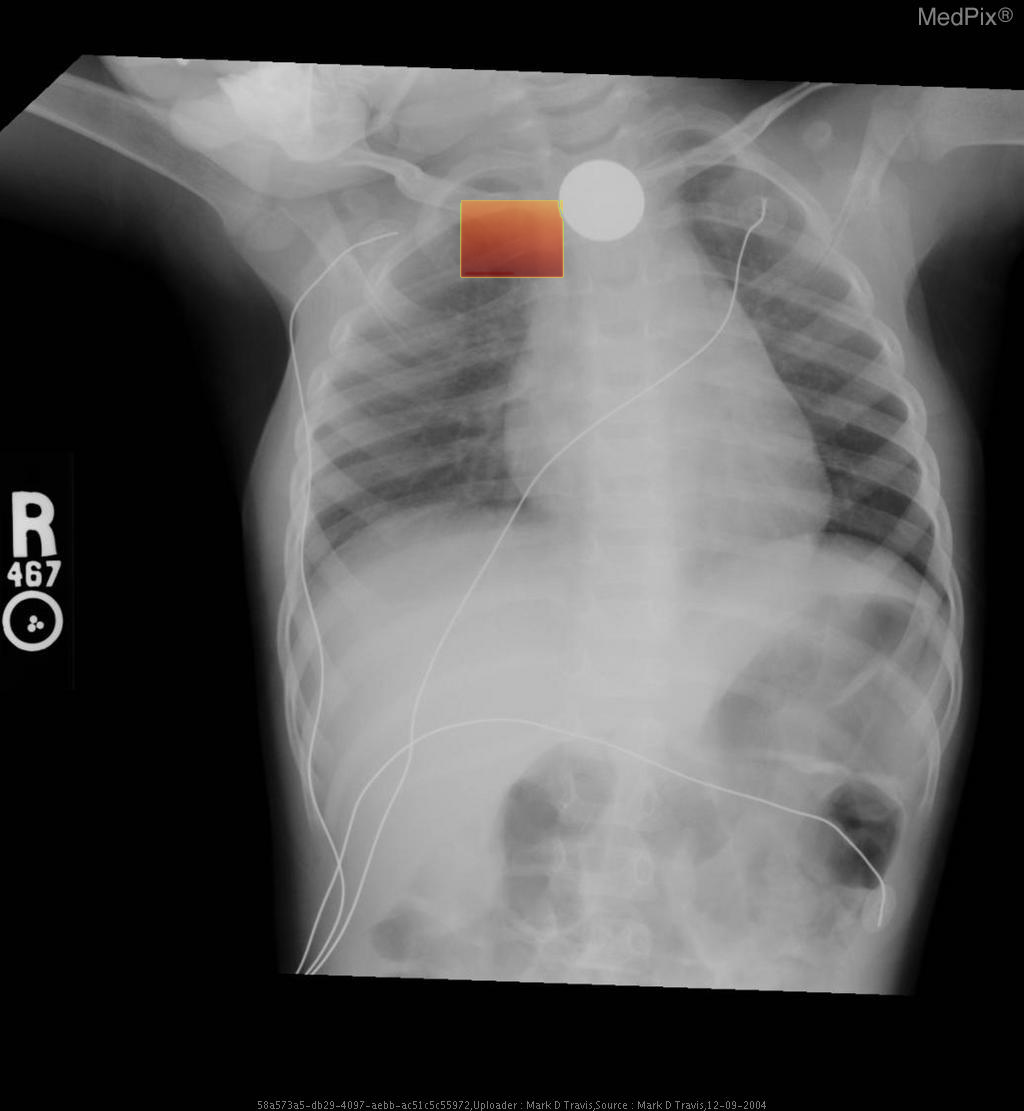

- A well-circumscribed, round metallic density (coin) projects over the upper thoracic midline, posterior to the tracheal air column — typical of an object lodged in the esophagus rather than the trachea.

- No evidence of significant tracheal narrowing, suggesting airway is patent.

- Lung fields are clear bilaterally; no focal consolidation, effusion, or pneumothorax detected.

- Cardiothoracic ratio within normal range for age.

- Normal diaphragmatic contour and position; no subdiaphragmatic free air visualized.

- Enteric and monitoring tubes appear appropriately placed without complication.

2) Most likely diagnosis and why:

Esophageal foreign body (coin) lodged in the upper esophagus. The round metallic opacity centered over the thoracic midline and seen full-face on AP view indicates an esophageal (not tracheal) location—since tracheal foreign bodies appear more radiolucent and typically lie off-midline or show edge-on orientation. The absence of significant respiratory compromise supports esophageal lodging. Context consistency: Consistent — matches the provided context of “coin ingestion” in a pediatric patient. Confidence: 95%

3) Next best diagnostic step:

Immediate clinical evaluation for airway stability is essential. If stable, proceed with a lateral neck/chest radiograph to confirm the anteroposterior position of the coin and exclude airway involvement. Endoscopic removal should be arranged urgently if the coin is confirmed within the upper esophagus, given aspiration and mucosal injury risk.

4) Key differential or confirmatory test:

A lateral chest or neck X-ray is the key confirmatory test — differentiating esophageal (flat, face-on coin) from tracheal (edge-on coin) position. If uncertainty persists, an upper endoscopy (rigid or flexible) provides definitive localization and allows immediate retrieval.

5) Possible treatment or management:

** Emergency management involves keeping the child NPO and arranging removal under sedation or general anesthesia. Endoscopic extraction is the preferred and safe technique. Post-removal inspection of the esophageal mucosa for ulceration or stricture formation is essential. Additional imaging may be needed if perforation, aspiration, or secondary complications are suspected.

📑 Guidelines Summary (uploaded diagnosis) — Esophageal foreign body

Nontraumatic chest wall pain is often musculoskeletal but imaging helps exclude other thoracic or soft-tissue causes when clinical suspicion remains.

- For typical localized pain and reproducible tenderness, no imaging is recommended initially.

- Chest radiograph is first-line if symptoms are atypical, persistent, or malignancy or infection is suspected.

- Non-contrast chest CT evaluates unclear findings, fractures not seen on radiograph, or concern for bone lesion.

- Contrast-enhanced CT or CTA is indicated if vascular etiology or chest wall mass with enhancement is suspected.

- MRI chest is preferred for soft-tissue, cartilage, or marrow involvement when radiograph or CT is inconclusive.

- Ultrasound can identify superficial soft-tissue masses, hematomas, or costochondral abnormalities in focal pain.

- Do not image acute, self-limited musculoskeletal pain without red flags such as trauma, fever, or systemic illness.

- Prompt imaging if red flags include palpable mass, prior malignancy, infection signs, or unexplained swelling.

- Follow-up imaging guided by progression, treatment response, or new concerning clinical features.

- Pitfalls include over-imaging benign costochondritis and missing early malignant rib or cartilage lesions.

🤖 Guidelines Summary (AI diagnosis) — Imaging for Pulmonary Embolism, Known Clot

Imaging selection for pulmonary embolism with known venous thrombosis focuses on confirmation, extent, complications, and guidance for treatment or follow-up.

- For known leg DVT with new chest symptoms, obtain CT pulmonary angiography (CTA) as first-line to confirm pulmonary embolism.

- Non-contrast chest CT is inadequate for detection; use contrast-enhanced CTA for diagnostic accuracy and clot burden assessment.

- Consider ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) scan if CTA contraindicated by severe iodinated contrast allergy or renal dysfunction.

- Time-critical evaluation: perform CTA promptly if hemodynamic instability or hypoxia suggests high-risk pulmonary embolism.

- MRI/MRA chest can be alternative for contrast allergy or pregnancy when radiation avoidance prioritized, though limited availability.

- Do not image if known PE and stable, already treated, and no new symptoms suggesting recurrence or complication.

- CT venography (CTV) adds little when DVT previously proven; reserve for evaluation of propagation in treatment-resistant cases.

- Red flags for urgent imaging: sudden dyspnea, syncope, hypotension, rising cardiac biomarkers, or right heart strain on ultrasound.

- Follow-up imaging only if clinical worsening or to evaluate chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension development.

- Pitfalls: motion artifact, suboptimal bolus timing, or poor opacification may mimic or obscure clot; repeat CTA if uncertainty remains.

Comments

No comments yet.

Please log in to comment